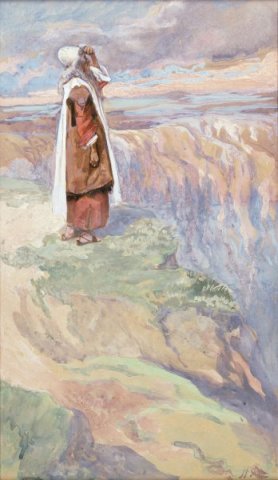

Photo Credit: Jewish Museum

The episode of Korachâs rebellion is so action-packed that it tends to overshadow other parts of this weekâs parsha. Among those sections is the storyâs immediate aftermath: The Jewsâ protest against Moshe and Aharon for killing âthe people of Godâ and Godâs resulting anger â which He communicates to Moshe and eventually translates into a plague after Moshe and Aharon fall on their faces. Then once the plague is underway, Moshe tells Aharon to protect the people not yet affected by bringing around the incense â the very same object that had just killed Korachâs two hundred and fifty allies.

Part of the story should sound familiar. This is not the first time God tells Moshe He wants to destroy the Jewish people. The normal continuation, however, is that Moshe prays for them and God relents. But this is not what happens here, and the result is almost 15,000 dead. Did something go wrong? One certainly feels that such is the case, though exactly what is not clear. Let us then try to make some order.

Many of the commentators find a disturbingly strong rationale in the Jewsâ complaint mentioned above. The complainers were essentially blaming Moshe for setting up a murderous trap for the two hundred and fifty men who contested the choice of Aharon and his sons as priests. As Bekhor Shor points out, Nadav and Avihu had already shown that unauthorized burning of the incense would be punished by death, whether one was a priest (like Nadav and Avihu were) or not (like the two hundred and fifty men, who only wanted to be priests). Hence the test would really prove nothing. But it would be effective in getting rid of Moshe and Aharonâs opponents! Yet, if so, two other questions follow: 1) Why did God get so angry at those that made the complaint; and 2) Why did Moshe not pray to stop the punishment before it started, instead of only finding an ex post facto (bediâavad) way to stop it.

Perhaps the answer to both questions is that when God told Moshe that He was angry with the Jews for their complaint, He was only presenting Moshe with the consequence of his own actions. Assuming â as appears from the text â that the test was designed by Moshe, it would seem that he was not careful enough in evaluating all of its consequences. Because the test was improperly designed, the rebellious complaint in its aftermath was something for which Moshe was at least partly responsible. And so when God gets angry at the people, all Moshe can do is fall on his face in grief at his own responsibility about what was happening.

But Moshe doesnât stay on his face for long. For even though it is too late to pray, that doesnât mean he should not do whatever he can to save as many of his people as possible. And that is exactly what he does when he sends Aharon out with the incense (also showing that the very same incense that kills can save, even in a situation where it is not commanded).

Of course, one should not think that those killed by the incense test or by the plague were innocent. On the contrary, if there was justice to the complaint about the danger of the test after the fact, it would have made sense before the fact as well. Indeed, it is likely that the test was chosen precisely to scare the two hundred and fifty men away from going through with it. That they chose to continue in their rebellion in spite of the danger makes them the ones who were ultimate responsible for their own deaths. Likewise, those that subsequently complained and looked for problems â rather than trusting a leader whom they should have known by now to have Godâs confidence â were hardly good candidates for divine favor either.

Even so, this does not take away from the fact that Moshe devised a plan with consequences unwanted by him or by God. It is true that Mosheâs possible misjudgment can be attributed to a feeling of urgency or anger in the face of a rebellion that seems to have come quickly on the heels of the greatly destabilizing spy debacle. But the truth is that it could have come about even without those extenuating circumstances. Moshe was human, and leadership comes with inevitable challenges. Lives are at stake and mistakes will happen. A good leader has no time to wring his hands and wallow in self-blame. Rather he must take responsibility and do what is possible to avoid further fallout â which is exactly what Moshe does here.

Though most of us do not lead entire nations and it is rare for our decisions to lead to loss of life, it does not at all mean that our decisions never bring about casualties. That is a given. What is not is how to react to it. Though it may not be immediately clear, I believe that we are well advised to follow in the footsteps of Moshe here. The greatest teachers are not the ones who teach us what to do when we succeed, but rather those who teach us what to do when we fail.