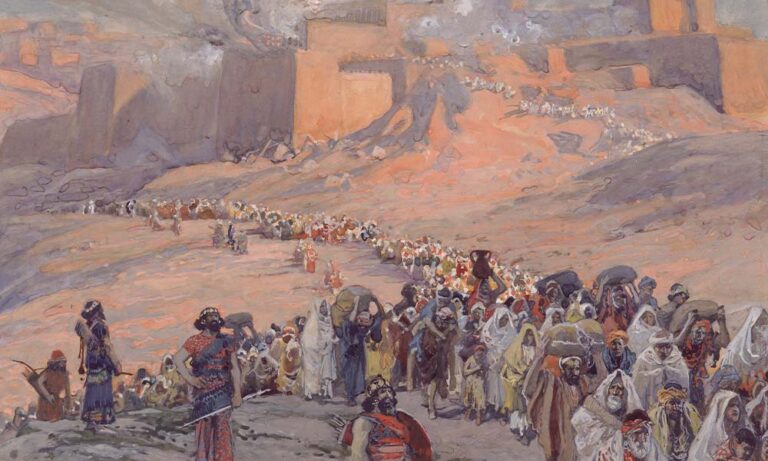

We are nearing the end of the “Three Weeks,” a period of mourning that commemorates the span between when the ancient Babylonians entered the city of Jerusalem in the 6th century BCE on the 17th day of Tammuz, and when they destroyed the Temple on the Ninth of Av, aka Tisha B’Av. Tisha B’Av also marks the destruction by the Romans of the Second Temple 600 years later.

If it wasn’t for the Babylonian exile, Judaism would look very different from the way it does today.

This first exile was a transformative time in our history. The story of how it came about is long and tragic—see the biblical books of Jeremiah and Ezekiel for more on the lead-up to war—but here’s an excerpt from Jeremiah (the “Weeping Prophet”) that chronicles part of the climax:

Jeremiah 39:6: The king of Babylon had [King of Judah] Zedekiah’s sons slaughtered at Riblah before his eyes; the king of Babylon had all the nobles of Judah slaughtered.

Jeremiah 39:6: The king of Babylon had [King of Judah] Zedekiah’s sons slaughtered at Riblah before his eyes; the king of Babylon had all the nobles of Judah slaughtered.

7: Then the eyes of Zedekiah were put out and he was chained in bronze fetters, that he might be brought to Babylon.

8: The Chaldeans burned down the king’s palace and the houses of the people by fire, and they tore down the walls of Jerusalem.

9: The remnant of the people that was left in the city, and the defectors who had gone over to him—the remnant of the people that was left—were exiled by Nebuzaradan, the chief of the guards, to Babylon.

10: But some of the poorest people who owned nothing were left in the land of Judah by Nebuzaradan, the chief of the guards, and he gave them vineyards and fields at that time.

The apex of the tragedy—the horrific siege and sacking of Jerusalem and the destruction of the First Temple—is vividly commemorated every year on Tisha B’Av through the mournful recitation of Eicha, also known as the Book of Lamentations, which is also attributed to the prophet Jeremiah.

I heard my first rendition of Eicha just last year, sitting on the floor of a house in Rockridge—a neighborhood on the border between Oakland and Berkeley, California. The house was BaseBAY, an organization that organizes events for Jews in their thirty-somethings. The mood was deeply somber, and I was very moved by the four chanters, who read out Eicha in a mournful mode and melody I later learned is unique to this particular reading on this particular day. (To hear what it’s like, click here. And check out this 1942 composition by Leonard Bernstein from his symphony Jeremiah, which uses the traditional chanting melody and which he wrote in response to what was happening to European Jews at the time.) For a more contemporary take, see these sections of Eicha re-written by survivors of October 7 and edited by Tamar Biala (editor of Dirshuni: A Book of Contemporary Midrash and translated into English by Yehudah Mirsky).

It’s worth pointing out that the Babylonian captivity left many lasting marks on our culture. For instance, the current names for the months in the Jewish calendar (Tammuz, Av, etc.) are not indigenous to Jews or even to Israelites; originally, but Babylonian. If it wasn’t for the Babylonian exile—which is well attested archaeologically and historically, by the way—Judaism would look very different from the way it does today. The Babylonian captivity changed us from a prophecy- and temple-based cult to a text- and Torah-based one, for one thing. It also prompted us to adopt a new Hebrew alphabet (the one in use today) and, yes, new names for our months. In fact, Judaism without the Babylonian exile would look a lot like—if not be identical to—Samaritanism.

There are about 3,000 Samaritans left today, and they are our Jewish cousins who were not schlepped to Babylon—that remnant alluded to in Jeremiah 39:10. To this day, Samaritan Torah scrolls are written in the Samaritan alphabet, which is close to paleo-Hebrew and which our ancestors used before this exile. Here’s what the Shema looks like in that alphabet:

ࠔְׁࠌַࠏ ࠉִࠔְׂࠓָࠀֵࠋ ࠉְࠄࠅָࠄ ࠀֱࠋֹࠄֵࠉࠍࠅּ ࠉְࠄࠅָࠄ ࠀֶࠇָࠃ

By the way, the month “Av” is named after the Mesopotamian deity Abu (just as the now-secular month March is named after the Roman god Mars). Very little is known about Abu today, but we know Tammuz was a Mesopotamian deity associated with agriculture and shepherds. Canaanites called Tammuz “Adon” (Lord—related to the word Adonai, Judaism’s primary euphemism for the Tetragrammaton. According to theologian Judith Plaskow, “Adonai” actually means “my Lords,” plural!).

Tammuz/Adon was also imported to Greece, where he became Adonis, a lover of Aphrodite and epitome of male beauty. A throughline of his cult from across the Levant and Mediterranean was the planting of gardens on the roof. In the hot summer, these plants would quickly grow and then dry out, symbolizing (or enacting, depending on your perspective) the life and death of the deity. Women, especially, would mourn Tammuz fiercely—Jeremiah bewailed this practice shortly before the fall of Jerusalem.

If you haven’t been to a reading of Eicha, I recommend finding one (inquire at your local synagogue or center of Jewish life) and claiming it as a powerful Jewish ritual that will enrich your life and set the tone for a few months of religious involvement.

In the meantime, whatever you do, don’t plant any gardens on your roof!

Opening image: The Flight of the Prisoners by James Tissot, c. 1896-1902

To regenerate means to renew, restore, or revive something that has been damaged or depleted. It can refer to physical, mental, emotional, or spiritual renewal and is often associated with healing and growth.

Source link