So what does this have to do with the apparently random commands in Vayikra 19?

Each of the commands in this chapter can be understood as a call to practice lehavdil and lehorot. The Torah is teaching us to distinguish, to divide, and to instruct. It is telling us that the moral life is not a matter of simple rules but of complex distinctions. It is not just about the right, the good, and the holy in themselves, but about the boundaries that separate them.

Do not mate different kinds of animals â the Torah is teaching us about the integrity of species. Do not plant your field with two kinds of seed â the Torah is teaching us about the integrity of the land. Do not wear clothing woven of two kinds of material â the Torah is teaching us about the integrity of human creativity.

Do not eat any meat with the blood still in it â the Torah is teaching us about the integrity of life. Do not practice divination or sorcery â the Torah is teaching us about the integrity of knowledge. Do not cut the hair at the sides of your head or clip off the edges of your beard â the Torah is teaching us about the integrity of the body.

Each of these commands is a call to practice lehavdil and lehorot, to distinguish and divide, to establish boundaries that preserve the integrity of the world as G-d created it.

And ultimately, this is the task of the Jew: to be a kohen, a priest, in the world, bringing order out of chaos, establishing boundaries that protect the integrity of creation, and sanctifying the world by living according to the word of G-d.

So the apparently random commands of Vayikra 19 are not random at all. They are a profound and challenging call to moral complexity, to the practice of lehavdil and lehorot, and to the fulfillment of our priestly mission in the world.

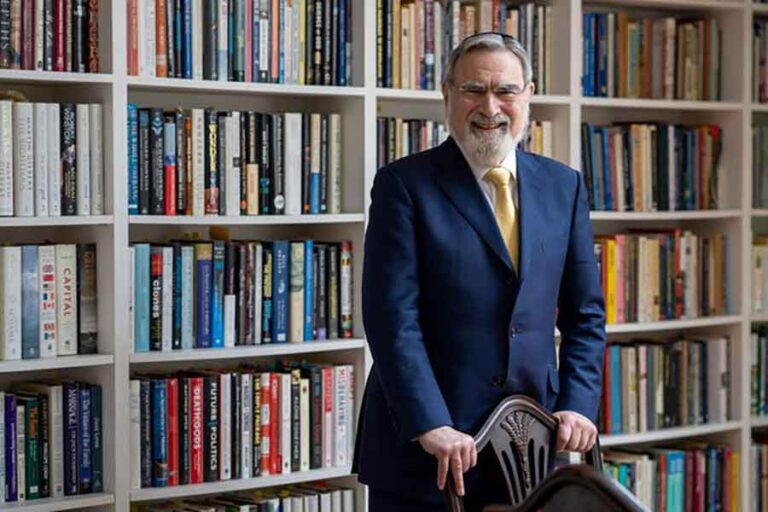

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, z”l, understood this profound truth, and he lived it in his teachings and his example. May his memory be a blessing, and may we all strive to follow in his footsteps, practicing lehavdil and lehorot in our own lives and in the world around us.

A good society, for the kohen, is one in which everything is in its proper place, and the kohen has special sensitivity toward the stranger, the person who has no place of his or her own.

The strange collection of commands in Kedoshim thus turns out not to be strange at all. The holiness code sees love and justice as part of a total vision of an ordered universe in which each thing, person and act has their rightful place, and it is this order that is threatened when the boundary between different kinds of animals, grain, fabrics is breached; when the human body is lacerated; or when people eat blood, the sign of death, in order to feed life.

In the secular West we are familiar with the voice of wisdom. It is common ground between the books of Proverbs and Ecclesiastes and the great Sages from Aristotle to Marcus Aurelius to Montaigne. We know, too, the prophetic voice and what Einstein called its “almost fanatical love of justice.” We are far less familiar with the priestly idea that just as there is a scientific order to nature, so there is a moral order, and it consists in keeping separate the things that are separate, and maintaining the boundaries that respect the integrity of the world G-d created and seven times pronounced good.

The priestly voice is not marginal to Judaism. It is central, essential. It is the voice of the Torah’s first chapter. It is the voice that defined the Jewish vocation as “a kingdom of Priests and a holy nation.” It dominates Vayikra, the central book of the Torah. And whereas the prophetic spirit lives on in aggadah, the priestly voice prevails in halacha. And the very name Torah – from the verb lehorot – is a priestly word.

Perhaps the idea of ecology, one of the key discoveries of modern times, will allow us to understand better the priestly vision and its code of holiness, both of which see ethics not just as practical wisdom or prophetic justice but also as honoring the deep structure – the sacred ontology – of being. An ordered universe is a moral universe, a world at peace with its Creator and itself.