In American culture, the word “hallelujah” is so associated with Christian prayer and music—and overall rejoicing and jubilation—that people often forget it is originally Hebrew. But Hebrew it is—really a combination of two words, hallelu, the imperative “Let us praise!” and Yah, a shortened version of the four-letter unpronounced name of God.

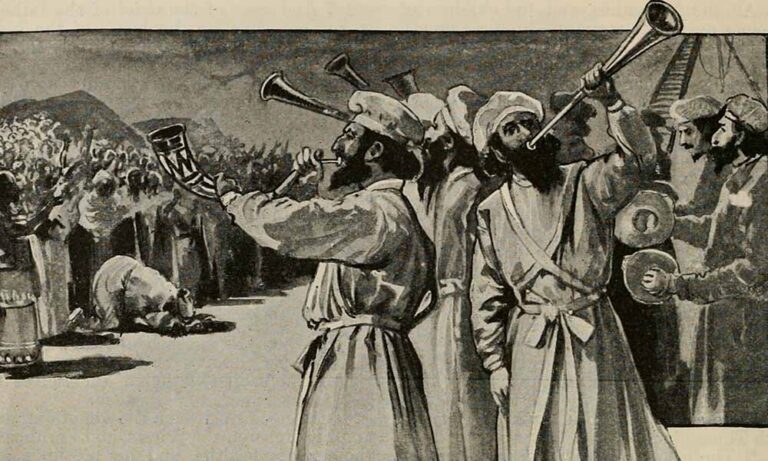

The word can be traced to at least the 5th century BCE, when it is thought to have been sung as part of a set of psalms by the Levites in the Second Temple. To this day, “hallelujah” features prominently in daily morning and Jewish festival prayers, but it may not have been a part of the original psalms. Rather, says Marc Brettler, professor of Jewish studies at Duke University, “hallelujah” could have been a joyous “religious cry,” a form of audience participation during the recitation of the psalms. While the word “hallelujah” appears 23 times in the Hebrew Bible, Brettler notes that it appears only in the Book of Psalms, and usually at the beginning or end of a psalm.

This suggests it may have been a vocal interjection or may have found its way into print “as a scribal division between compositions, in order to conserve space and expensive parchment.” But after the destruction of the Temple and the rise of rabbinic Judaism, Jewish liturgy became codified and “included the chanting, reciting or actual singing of psalms that included ‘hallelujah,’” says liturgy scholar Lawrence Hoffman.

The rapid and widespread dissemination of the use of “hallelujah” as a congregational response came through Christianity. Just as Jews recited psalms in prayer services, so did early Christians (or Jewish Christians, as they were then known). “We know that psalms were being used in the Eucharistic liturgy”—the commemoration of the Last Supper—“by the end of the 2nd century in North Africa,” says Maxwell Johnson, a professor of liturgical studies at the University of Notre Dame. By the 4th century, psalms using the word “hallelujah,” known by Christians as the “laudate” (praise) psalms, were being sung in morning prayers. From the 4th or 5th century onward, a combination of a psalm and a congregational “hallelujah” response preceded “readings of Christian Gospel verses in the Eucharist,” says Johnson. Of course, he adds, Christianity used the term differently, transliterating the word as “alleluia,” based on the spelling in the Septuagint (the translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek), and viewing its recitation as a way to greet the presence of Christ.

Meanwhile, “hallelujah” gained a new dimension. Eric Werner, a noted Reform musicologist, wrote in a 1946 Hebrew Union College journal article that “‘hallelujah’ assumed in both Hellenistic Judaism and in the Early Church a distinctly

mystic-esoteric character, greatly enhanced through its ecstatic musical rendition.” An example was “Jubilus,” the joyous, ecstatic “hallelujah singing” of the single word “alleluia” with prolongation of the last syllable, which became popular in the Middle Ages. In fact, Johnson says, Christian uses of “alleluia verses” proliferated so much that variations in their singing are used today to study the ways in which Christian liturgy developed in different churches and monastic communities throughout medieval Europe.

From the Renaissance on, the word seemed to open up the musical heavens. Numerous hymns, canons, oratorios and other elaborate musical church pieces were composed containing or consisting entirely of the word “alleluia.” Pieces such as Mozart’s 1773 motet, “Exsultate Jubilate,” and Walton’s 1943 “Belshazzar’s Feast” are among the best known, as is, of course, the “Hallelujah Chorus” of Handel’s 1741 Messiah, in which “hallelujah” is sung 48 times.

In the 1500s, the word “hallelujah” finally debuted in English, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, albeit with a variety of spellings and pronunciations. (The German spelling, using the soft “j” rather than “y,” says Brettler, may be the source of the modern English spelling.) The word traveled to America with the Pilgrims and became deeply embedded in religious music and eventually in the American songbook. Hallelujah singing comes down to us today in many forms. Some are exultant, such as “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” and the Negro spiritual “Glory, Glory, Hallelujah

(I Laid My Burdens Down).” Others, such as the folk songs “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore” and “Nobody Knows the Troubles I’ve Seen,” reflect a quieter faith, similar to that expressed in many biblical psalms, that hardship will ultimately end. But in every case, it is the emotive praise of “hallelujah” that elevates the spirit.

In contrast, in Leonard Cohen’s controversial “Hallelujah” (1984), the “hallelujah” is not praise, but resignation; not joy, but consolation. Cohen’s “broken” hallelujah resonates so strongly and is somehow affirming, not in spite of its irony, but because of it, as illustrated by its popularity throughout the world.

The lasting power of “hallelujah” has something to do with the fact that from its very beginning, it was never just a word.

Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, the 19th-century German rabbi and founder of Modern Orthodoxy, translated its root, the letters H-L-L, to signify rays or emanations from God. And, throughout its history, “hallelujah” has served as a radiating force as it is said or sung—in prayer, in celebration, as consolation or in everyday conversation.

It is no wonder that a word that for thousands of years has embodied spiritual power comes to people’s lips almost without reflection when they have a narrow escape or a chance to celebrate one of life’s small triumphs. Hallelujah!

Opening picture: Levites rejoicing at the Second Temple. (Photo credit: Wikimedia)