These efforts to transform interfaith relationships have been important in fostering understanding, respect, and trust between Muslim and Jewish communities. However, recent events have highlighted the challenges that still exist in building and maintaining these relationships. It is clear that ongoing efforts are needed to address the complexities and tensions that arise in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. This includes acknowledging the pain and suffering experienced by both Palestinians and Jews, and finding ways to work together towards a more peaceful and just future for all involved.

In this current climate, the efforts of the Muslim-Jewish Advisory Council to address anti-Muslim bigotry and antisemitism in the U.S. have taken a backseat to the escalating tensions in the Middle East. The focus has shifted from building bridges between the two communities to dealing with the fallout from the conflict in Gaza. Imam Omar Suleiman, a key figure in the interfaith dialogue, has explicitly stated that all work is now secondary to ending the violence in Gaza.

The rift between Jewish and Muslim communities in the U.S. has widened as a result of the conflict, with some Jewish leaders feeling betrayed by their Muslim counterparts’ support for anti-Zionist rhetoric. Rabbi Yoffie, who had once championed Muslim-Jewish dialogue, has now distanced himself from his Muslim contacts in light of the recent events. The once-promising prospects of Muslim-Jewish relations in the 21st century now seem uncertain and fraught with challenges.

The complexities of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict have further strained relations between Jewish and Muslim communities, making it difficult to find common ground. The inability to agree on basic facts and the deep-seated animosity on both sides have made reconciliation seem increasingly unlikely. The events of October 7 have highlighted the deep divisions and entrenched positions that have come to define the relationship between these two communities.

Regenerate

Reaching any consensus on what has happened may be impossible.

In the United States, the polarization between Muslims and Jews is complicated by a sense on both sides that they are alone. Jews are facing a dramatic increase in antisemitism, notably evident in some pro-Palestinian rallies around the country. In California, the Oakland City Council, after passing a resolution calling for a Gaza cease-fire, rejected an amendment condemning Hamas for the October 7 attack after numerous speakers defended Hamas as a legitimate protest movement against Israeli rule. American Muslims may also feel isolated, convinced that Palestinian suffering is not adequately recognized. Aziza Hasan sees it in the reaction to Israeli and Palestinian flags being flown in public. “I see the blue and white everywhere,” she says, “but then when someone flies the other one, the red, green, black and white, people bristle. And I think, ‘You were already flying one flag, why can’t you see the second one and make space for it?’ People don’t see how they’re coming off to each other.” In her public prayer at the Los Angeles City Hall, Hasan said she worries about “the fear and anger that stifle our compassion.”

Dialing back expectations of interfaith partners

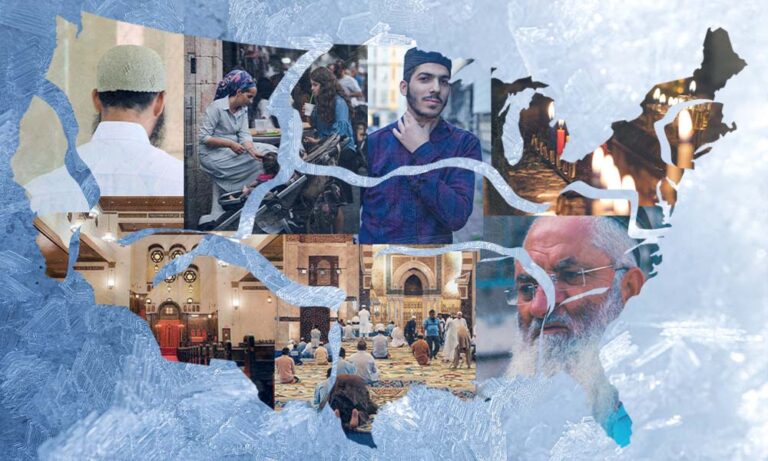

My conversations over the past few weeks with 18 prominent Jews and Muslims, U.S.-born or immigrants, suggest that interfaith efforts are in a fragile place, at least for now—“a crisis point,” in the view of Yossi Klein Halevi. “The level of trust between the two communities on the leadership level hasn’t been this low since I’ve begun following the relationship,” he says. Imam Saffet Catovic, who was impressed by the way American Jews rallied in support of his fellow Bosnian Muslims in the 1990s, is likewise discouraged. “The expectation of some was that these sentiments were just going to last a few days,” he says, “but I don’t see the frustration, the anger and the pain disappearing.”

Barring such progress, those American Jews and Muslims who remain committed to each other have dialed back their expectations to focus more on their personal relationships and less on establishing preconditions for a broader dialogue. “We need to show up in different ways,” says Aziza Hasan. NewGround under her direction does not do “litmus tests,” she says. “We’ll have a conversation with anyone who’s willing to have a conversation, as opposed to setting parameters for who we want to talk to.” Rabbi Straus, who relinquished the chairmanship of the National Council of Synagogues in June 2023 and now serves as the organization’s executive director, has been meeting informally since October 7 with a group of Muslims and Arabs in Philadelphia, most of whom he has known for many years. “We want to better understand our communities,” he says, “and we want to be neighbors. Just as we were neighbors before October 7, it’s even more important that we be neighbors after October 7, as difficult as that might be.”

One factor that favors the Muslim-Jewish bond here in the United States is that the groups share a minority status and are therefore connected in their common vulnerability to bias. Research has shown that antisemitism and Islamophobia in the United States rise and fall in tandem, a fact Rabbi Straus emphasizes with his Muslim neighbors. “The forces of antisemitism and Islamophobia mean that whoever is coming after me first is coming after them second,” he says. “And whoever is coming after them first is coming after me second.” Imam Catovic says that’s a message he emphasizes as well. “Muslims are Friday Americans. Jews are Saturday Americans. Everybody else is a Sunday American,” he notes. “So we Friday and Saturday folk know what it means not to be Sunday folk.”

In the end, the deepest bond between Muslims and Jews everywhere is that their religious traditions are intertwined. The ISNA-URJ collaboration, after all, was titled “Children of Abraham.” The San Francisco-based Palestinian-American human rights activist Hala Hijazi, still deeply grieved by the loss of so many of her relatives in Gaza, says it is that connection that keeps her focused in her ongoing interfaith relationships with Christians and Jews. “While this has devastated me personally,” she says, “I know the work must continue. We must continue opening our congregations so that when we get on the other side of this, we’re still intact. This is faith in action. At the end of the day, a dead child is a dead child. We are all God’s children.”

To regenerate means to restore or renew something to its original or better condition. This can refer to physical regeneration of cells or tissues, as well as the renewal or revival of something that has deteriorated or worn out.

Source link