Orthodox Jewish society, both in Israel and outside of it, often leads to truly unique encounters of study, assembly, and of course prayer. For instance, a stone structure from the British Mandate, located in the ancient city of Beit Sheâan, contains a truly fascinating sight: the Halleluyah synagogue, a Sefardic-Chassidic synagogue most of whose congregants consider themselves to be the students of the students of Rabbi Nachman of Breslav.

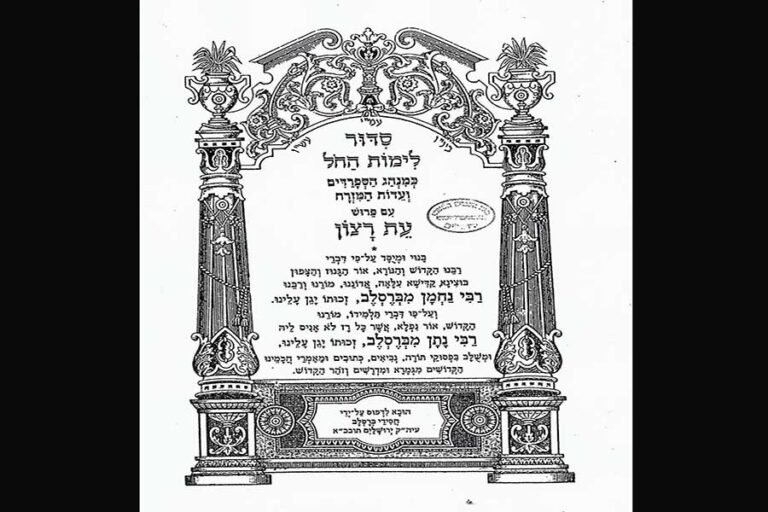

New prayer houses such as these, which mix and match different traditions of prayer and custom, continue to be created all the time in many places. It is thus entirely natural that the siddur bookshelf also be enriched with new siddurim expressing this new trend, with approaches to prayer which previous generations would have found difficult to imagine. One of these is the Eit Ratzon siddur, which combines the Sefardic-Mizrachi tradition with the spiritual, Chassidic world of Breslav.

The siddurâs first edition â containing a long commentary by Rabbi Eliezer Shlomo Schick, otherwise known as the âTzaddik of Yevanel,â who was behind its production, appeared twenty years ago, on the basis of a standard Ashkenazi Chassidic siddur. But as Rabbi Schick describes in his introduction, many Chassidim of Mizrachi origin appealed to him, asking to combine the traditional world they were raised in and their renewing spiritual one: âAnd now our people from the communities of the Mizrach requested, to integrate the commentary also on the nusach of prayer they pray in, and therefore if you find some change in the commentary, [know] that this is only for the Sefard nusach, take no note of this, for one memory will arise [to G-d] for here and for here ⦠with all this, we also organized the commentary also according to the nusach of the communities of the Mizrach, more or less.â

The ideological challenge in even producing such a unique siddur can be seen in the truly impressive number of haskamos from Mizrachi Gedolim to be found in its first pages, including letters from Rabbi Ovadiah Yosef, Rabbi Yitzchak Kaduri, Rabbi Shalom Mashash, and Rabbi Meir Mazuz. True, most if not all of these letters attested to Rabbi Schickâs overall Torah repertoire (and his ability to arouse the people to do teshuvah) and not the siddur itself. However, it turns out that the prominent inclusion of these letters at the beginning of the siddur was sufficient to declare (for the congregants most of all!) that their increased attraction to the teaching of Rabbi Nachman is not supposed to and does not have to come at the expense of their ethnic identity or their basic obligation to their familyâs traditions of halacha and prayer.

The original integrated siddur was published in 1999, including only weekday prayers, alongside commonly accepted additions. Later, machzorim for the holidays and the High Holidays appeared, just like their Ashkenazi counterparts. One of the siddurâs clear advantages lies in the relatively large print format and its big and clear font, which makes it easier to pray and read the commentary.

The siddurim can be acquired in two places, one in Israel and one in the United States, whose names attest to the social and geographical processes taking place among the Jewish People even now: Yevanel-Ir Breslav-Galil in the Galilee on the one hand, and the Mesivta Heichal HaKodesh of the Breslav Chassidim in Brooklyn, on the other.

âEit Ratzonâ is not a truly integrated siddur in terms of nusach, but rather a traditional Mizrachi siddur wrapped in a new Chassidic-kabbalistic commentary. It is not even the only siddur serving the Mizrachi Breslav community in the past few decades. All such siddurim mix between the spiritual and halachic worlds which were once as distant as, well, east and west, and which are being brought together in the new world being created in the Land of Israel.

My deepest thanks to my friend Ido Veker, for helping prepare this piece.

This article was originally published on JFeed.com.