Everybody who knows the Passover Seder knows the famous text of “Why is this night different from all other nights”. Some may even recall that there are four such expressions and even a few of us may remember their specifics.

The simple understanding of these questions is a comparison between Passover night and all the other nights of the year but a slightly deeper dive opens up a whole other perspective.

Whenever we see something grouped in “four” it should set off a bell letting us know there is a subtle hint here to the four letters of God’s Holy Name. And therefore, if we understand in brief what each of God’s four-letter Name refers to, we will also see the tie-in to the “four” we’re talking about – the four questions.

| Letter from God’s Name | Four Questions (Some Haggadot have a different order) |

| Yud | On all nights we eat chometz or matzah, and on this night only matzah? |

| Heh | On all nights we eat any kind of vegetables, and on this night maror? |

| Vav | On all nights we need not dip even once, on this night we do so twice? |

| Heh | On all nights we eat sitting upright or leaning, and on this night we all lean? |

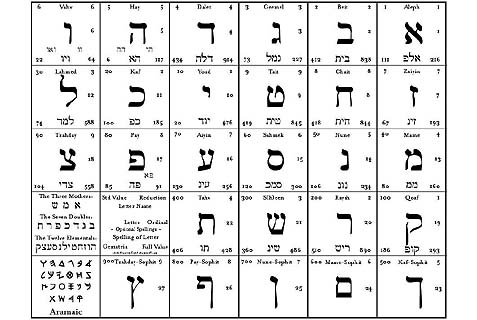

The first letter of God’s Holy Name, Yud, is the only letter in the Hebrew alphabet which does not extend down to the baseline suggesting that it is ‘wisdom from above/beyond this world’. The next letter, of which there are two in the Name, is Heh which is connected to that which is ‘hidden’ because the Heh is pronounced like the sound of an exhale which hides the words behind it. The first Heh refers to those things in the higher worlds which are hidden from us while the last Heh refers to those things and/or events whose meanings are hidden from us in this world. And the third letter, Vav, is like a conduit, or pipe that brings the higher wisdom of the Yud down into this world as practical wisdom.

Now, with this in mind, we can look at the four questions. If we re-read the first question, it can also be understood as referring to why this ‘night’ is different from all other ‘nights’, not as a reference to the year, but to the events in the history of the world which can be called night, a time of no reason, no compassion, and no understanding. And, as if we could compare one night/evil with another, the Haggadah suggests that this night’s evil is fundamentally different from all other nights’ evil. How is that?

Night suggests life in this world when God is hidden. In general, when we study the darkness of such nights, we are able to catch a glimmer of what God may have had in mind for us.

To see God’s Hand in our world is represented in the “bread of faith” known as the Matzah. To lose sight of God’s Hand in this world is represented by the Chometz. This is because both Matzah and Chometz are made from the same ingredients of flour and water but the difference is that Chometz is left to rise which symbolized the swelling of a person’s ego that blocks out any awareness or appreciation of God.

Therefore, on the ‘normal’ nights of our lives, we sometimes see the Hand of God and sometimes not. On this night, however, is the night of redemption. This, as the Talmud in Pessachim says, is the night which is called “light” because on this night we are able to solve the mystery of what is occurring in our darkness and to see/realize that all is in the Hand of God and therefore we only eat the bread of revelation – Matzah. This is seeing the power of the Yud in every activity, seemingly good or bad, in our world, and thus knowing it is all for the good.

The same idea continues to the second question, which corresponds to the first of the two letters Heh. Here we ask why we eat all types of vegetables while on this night we eat only Maror. Maror is known as the bitter herb. Normally a bitter food is not a food of choice and yet we chose only this herb for Passover. The reason is that now that we have connected to the world of higher wisdom (the Yud) we are able to eat the bitter and realize that although it “tastes” bitter, it is really coming to us as a hidden healing. But without a connection to the higher wisdom we would not even begin to appreciate that the bitter could be good.

Now comes the Vav, the world of action, and it is symbolized here by the dunking of the food into liquid before being eaten. Classically people tend to use a hardboiled egg for the food and salt water for the liquid. The egg is known as mourner’s food because, on one level, the egg has no mouth and the mourner is in so much pain he too has no mouth through which to express his grief. And the salt water only seems to exacerbate the suffering.

However, there was a time when the Jewish nation had just come out of Egypt and encountered water they could not drink because it was salty. God told Moshe to throw a branch into the water to make it drinkable. Certainly throwing a piece of wood into salty water will not take away the salt and clearly this was a miracle, but the meaning behind that miracle is that the tree represented the Tree of Life, which is equated with Torah and its wisdom.

Having attached ourselves to the higher wisdom of the Yud we can dunk our suffering (the egg) into the salt water and “taste” the Mitzvah instead of the bitterness. The act of dunking is symbolic of bringing something from above to below which, as explained above, is what the Vav is all about, drawing the higher worlds into the lower worlds. Therefore, even if we know that our suffering comes from Above and it still seems bitter (salt water) in this world, on this night we can understand the entire experience in the light of healing and holiness.

The final Heh, like the earlier one, is about the hidden, but in this case it is the hidden in our world. On all other nights we sit or lean but on this night we only lean. Sitting is equated in Jewish thought with acquiring higher wisdom in this world. We see in the Talmud Chagigah that when the rabbis would discuss very deep esoteric teachings they would sit. We see that the school of Holy Knowledge is called a Yeshiva, “a place to sit”, and we find that the day which opens the windows to Heaven, Shabbat, is about sitting. In fact, the first two letters of Shabbat spell “to sit” in Hebrew.

Leaning, however, is about freedom, and the only freedom we know is the freedom given to us by the Torah, as the Mishna says: “Do not call them engravings (referring to the two tablets) but rather freedom.” The final Heh hides the fact that God is King of all worlds and especially our world. This is why the Hebrew word for hidden (עלם) is very similar to the word world (עולם).

In Jewish mysticism, this world is referred to as the Kingdom because in the End of Days the whole world will recognize God as King. Therefore, prior to this period of time, we are able to receive wisdom in a position of “sitting” and sometimes even understand it at its highest level represented by “leaning”. This higher wisdom is a type of freedom that is expressed in our “leaning”. On this night, because we access wisdom on its highest level, we are free people who only “lean”.