Davidai was concerned that the presence of Betar supporters could escalate tensions at the event. He approached them and asked them to leave, explaining that their presence was not helpful. They refused, claiming that they had a right to be there and support Israel.

As tensions rose, Davidai decided to end the counter-protest early to avoid any potential violence. Despite this, Betar supporters continued to follow him and his group as they left, shouting insults and threats.

After the incident, Davidai reached out to the Anti-Defamation League for support and guidance on how to handle the situation. The ADL advised him to document the incident and report it to campus security, which he did.

Since then, Betar supporters have continued to target Davidai online, spreading false information and threats against him. Despite this, Davidai remains committed to advocating for Israel and fighting against antisemitism in all its forms.

As the conflict between pro-Israel and pro-Palestinian groups continues to escalate, it is clear that organizations like Betar are playing an increasingly prominent role in shaping the narrative. Whether their tactics are effective or harmful remains a topic of debate, but one thing is certain: the fight against antisemitism is far from over.

“All they did was scream ‘F— Gaza,’ ‘Gaza is ours,’ ‘Here’s a beeper for you,’ ‘Deport them all,’ ‘ICE, ICE, ICE,’” he said. “Just violent rhetoric.”

Davidai is no stranger to provocation: Last fall, Columbia barred him from campus after months of his vocal criticisms of the university’s handling of antisemitism. Yet he views Betar as a serious obstacle to the movement he was trying to build, not least because they were adapting the same tactics as the pro-Palestinian side: expressing support for a terror group and hiding their faces as they did so.

“I think it’s hypocritical to spend 16 months blaming all protesters who are in this Free Palestine movement for not policing their own protesters, but then let hatred and violence take root in yours,” Davidai said. “I said, ‘Look, you’re doing exactly what we’re telling them not to do….’ At some point I asked them, ‘Go do your thing, but don’t be associated with us.’ They refused.” (Torossian disputes Davidai’s account of the weekend’s protests, saying that Betar had organized independently of the professor’s group, and that Betar’s own numbers were closer to 50.)

After the rally, Betar and its followers began targeting him online. On Instagram he blasted them for only joining counter-protests, while never showing up to rallies for Israeli hostages. The rhetoric has only escalated from there, as Betar has mobilized its followers against him, in public and private. “You will be disrupted at all future speeches,” Torossian messaged Davidai on WhatsApp, according to communications shared with JTA. “You are a radical.”

Davidai has also urged his followers against supporting any further killings or mass expulsions in Gaza, a stark contrast to Betar’s own stated views. Yet in the comments, many of Davidai’s own followers have begun taking Betar’s side, accusing him of naively trying to make peace with the enemy.

Like Davidai, Betar’s activism sprang out of last spring’s encampment movement — and its evolving pro-Israel counterforces. Last spring the Shirion Collective, a pro-Israel group similar in temperament to Betar, counter-demonstrated at the University of California, Los Angeles encampments alongside other pro-Israel contingents. The conflict devolved into a violent brawl with several arrests.

Witnesses at the time said the UCLA pro-Israel counter-protesters chanted “Second Nakba,” a reference to the Arabic word for “catastrophe” — how Palestinians refer to their mass displacement at the State of Israel’s founding. In the Forward, David Myers, a Jewish professor at UCLA and president of the New Israel Fund, called the pro-Israel contingent “a violent band of thugs intent on inflicting damage” and condemned the school for not being prepared to intervene sooner.

Betar US hadn’t yet been officially constituted at the time, and Torossian said the group had no ties to what happened at UCLA in the spring. But when anti-Zionist students set up a sukkah in the fall, the new group issued its own threat: “We demand police remove these thugs now and if not we will be forced to organize groups of Jews to do so.”

Recently, revisiting its statement, Betar declared, “We are proud of what we have done at UCLA. Yes if the police don’t do their job Betar will.”

Davidai still believes his own movement will win over Jews in the end. Betar, he believes, is mainly composed of “frustrated keyboard warriors” with a misguided view of activism. “A lot of people confuse peacefulness and nonviolence with submissiveness. They confuse community organizing as weakness,” he said.

“Organizations like Betar are not interested in the free marketplace of ideas,” Davidai added. “They’re interested in canceling people they disagree with, ad-hominem attacks, shouting, counter-protesting.”

Still, he said, “They’re not as bad as people who support Hamas.”

Regenerate

Those include a non-Jewish military veteran in Massachusetts arrested after shooting a pro-Palestinian protester who jumped him and a rabbi and his son in Milwaukee who were arrested after destroying a real-estate owner’s pro-Palestinian mural that depicted a Star of David turning into a swastika. Last week a Betar affiliate counter-protested at a demonstration outside the home of a Jewish regent of UCLA, where a pro-Palestinian group was directing threats like “Divest now, or you will pay.”

Some Betar recruits, such as Schanzer, told JTA they only became truly invested in pro-Israel causes after Oct. 7. In addition, what connects most of them is a desire to take the fight against antisemitism to the streets, and a deep antipathy toward establishment Jewish institutions that they say aren’t acting with a similar level of urgency.

Peter and Zechariah Mehler, Jewish Milwaukee residents, freely admit to having torn down a pro-Palestinian mural depicting a Star of David turning into a swastika. (Courtesy)

“My politics and Betar’s politics are very different. I’m not a right-wing guy,” Zechariah Mehler, who encountered Betar after his own Milwaukee mural incident went viral, said about his initial hesitation in joining the group.

But, he said, Torossian assured him there was a place for him in Betar, since both believed Jews should stop “just being meek and allowing ourselves to be threatened and walked over. So I said, sure.” Betar helped the Mehlers raise legal fees, and Torossian lobbied for their case in the press, calling them “heroes.” Since then, Mehler has happily promoted Betar on social media.

“I think Betar collects the people whose reaction to threats is ‘fight,’” Mehler mused, adding that such people sometimes “are a little militant.” Adapting a “Sopranos”-like, tough-guy accent, he imitated a Betar member: “I’m gonna fight this thing. No one’s gonna tell me what to f—ing do.”

Before he left the group, Glick insisted that Betar, which is a registered nonprofit, does not endorse political candidates or policy proposals in either the United States or Israel. “We’re not for or against Trump. We’re not for or against Biden or Bibi. That’s not our position,” he said. “At the end of the day, we are an educational organization promoting Zionism.”

But Torossian has represented figures in Trump and Netanyahu’s orbits, including Eric Trump and, at one point, Netanyahu’s Likud party. And since Glick’s departure, Betar’s social media has proclaimed, “We stand with @netanyahu and @RealDonaldTrump.”

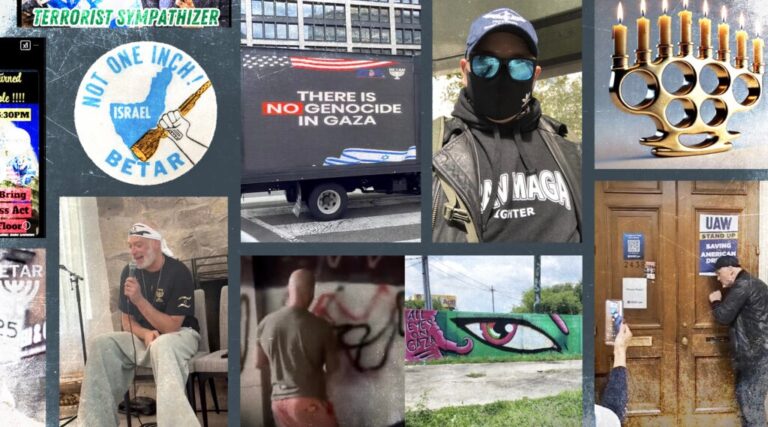

Betar’s accounts frequently voice bromides closely aligned with the Jewish and Israeli far right, recently tweeting, “Both sides of the Jordan River are ours” (a quote from a song attributed to Jabotinsky) and spotlighting “friends” clad in gear from the JDL.

Asked about the JDL, Torossian, who also said he does not write Betar’s tweets, claimed he was unaware of any similarities between his group and the far-right militant gang founded by the late Rabbi Meir Kahane. He also rejects any characterization of Betar as “extreme,” “far-right” or a “militia.” Betar’s social media, meanwhile, recently shared a clip of a member expressing nostalgia for “the Rabbi Meir Kahane days.”

“We don’t want peace. We don’t want co-existence,” Betar declared after a recent chaotic hostage release from Gaza. “It’s us or them. Choose a side. Society or the rapestinians.”

Betar has also endorsed a policy proposal, floated by Trump multiple times including during a joint press conference this week with Netanyahu, to force all Palestinians in Gaza to resettle in Egypt, Jordan or other neighboring countries. The view is far to the right of nearly every large American Jewish group and the international community, which has stated for months that any permanent displacement of Gazans as a result of the war would constitute ethnic cleansing.

“I think it’s a very good idea,” Glick said about Trump’s proposal. “It’s a giant pile of rubble. How can you rebuild there?”

Betar’s messaging occasionally stretches to other right-wing talking points that have little to do directly with Judaism, like a stance against “transgenderism” and a swipe at progressive Rep. Ilhan Omar — not for her vociferous Israel criticism, but because of her efforts to help fellow Somali refugees. The group has even backed figures whose right-wing nationalist views overlap with antisemitism, like British anti-immigration advocate Tommy Robinson (who in 2023 was arrested after attending a march against antisemitism against the wishes of the march’s Jewish organizers).

This shouldn’t be surprising, Myers told JTA. The UCLA professor said he sees Betar as an outgrowth of a long culture of “toxicity” and “disinhibition” in American politics. He believes that spirit has, over the last few years, animated not just groups like Betar but also institutional Jewish groups’ way of thinking about Israel’s critics.

“It rhymes with a lot of the efforts of more mainstream organizations which, in my mind, equate support for Palestinians, Palestinian self-determination, with a pro-Hamas, pro-terrorism stance,” he said. “Betar takes rise out of that legitimization of the claim that disagreeing with Israel’s actions in Gaza is akin to antisemitism.”

Billie Little, a Jewish graffiti artist, shows off a New York mural she made in collaboration with Betar. Though Little says she disagrees with Betar on many issues, she is also grateful for the group’s existence. (Courtesy)

For some pro-Israel activists, Betar can be complicated. “I see them post videos, and it’s like, why are you filming yourself screaming at people? That doesn’t look good,” Billie Little, a pro-Israel street artist in New Orleans who has joined forces with Schanzer, told JTA about Betar.

“There are times I feel like, ‘OK, I don’t know if I want to be all-in on this.’” However, Little accepted Betar’s help in raising money for her and Schanzer to acquire paint supplies and even helped Betar put up a Zionist mural in her hometown of New York City, despite strongly disagreeing with them on many stances, particularly concerning their endorsement of President Trump’s plans for Gaza.

Little was spurred to work with the group despite her disagreements because of its sense of urgency. She noted that some Jewish groups, including federations, are taking a more quiet and civil approach, leaving many Jewish people feeling helpless. She felt the need to stand up for herself and take action.

On the one-year anniversary of Oct. 7, Betar pinned a post to its X profile, showing a screenshot of a pro-Palestinian group receiving threats from Zionists, with the commentary “#JewsFightBack.”

In 1923, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, a Russian Jewish Revisionist Zionist leader, established Betar as a right-wing faction of Zionism. Jabotinsky believed in physically fighting back and never taking a blow sitting down. He organized Betar as a militant group willing to answer to him.

Hillel Halkin, a writer and author, stated that Jabotinsky believed in fighting back against violence and insults. He believed in practical solutions and using violence if necessary. However, he would probably have disapproved of Betar’s intimidating tactics at pro-Palestinian protests.

Despite its resurgence in the United States, Betar’s tactics have been met with mixed reactions. Some believe that Jewish militancy could combat anti-Israel sentiments, while others feel that it may not be the best approach for young American Jews.

Jabotinsky’s legacy is revered by Betar members like Torossian, who views him as the most formidable Zionist ever. Betar’s website praises Jabotinsky’s vision and encourages followers to take his Hebrew oath. For Torossian, the ultimate goal is to be safe in the Jewish state and to fight back against any threats.

Glick, who also grew up in Betar, drifted away from the organization as an adult but reconnected with Torossian at a counter-protest. Torossian’s recent arrest at Syracuse University further convinced him of the need to relaunch Betar for the current age. Both men believe in standing up for themselves and fighting back, echoing Jabotinsky’s beliefs. But his legacy lives on in organizations like Betar, which continue to promote a strong Jewish presence and advocacy for Israel. While their tactics may be controversial, their commitment to their cause is unwavering. As they navigate legal battles, campus controversies, and social media spats, Betar remains steadfast in their mission to defend Israel and the Jewish people. Whether you agree with their methods or not, one thing is clear – Betar is not backing down.

He died of a heart attack in 1940 while visiting a Betar camp in New York, at the age of 59, eight years before Israeli statehood.

At the time of his death, Halkin said, the movement he championed was getting away from him — particularly as Betar members stoked rising tensions between Arabs and Jews in Mandate Palestine in the 1930s, something Jabotinsky, who advocated for a degree of Arab-Jewish coexistence, ardently opposed. “If someone had to go and put a bomb in an Arab marketplace and set it off, it was generally Betar that did this,” Halkin said.

Betar’s influence waned after the founding of the State of Israel, as most Israelis embraced a more left-leaning kibbutznik form of Zionism and their fascist-leaning approach fell out of fashion. Chapters across the Diaspora remained active, and some influential Israelis, including former Prime Minister Menachem Begin, the late Israeli statesman and diplomat Moshe Arens and the scholar Benzion Netanyahu, the current prime minister’s father, have traced their political evolutions to the movement. Beitar Jerusalem, the professional soccer team infamous for its racist hardcore fans, also takes its name from the movement.

Betar US hopes that tomorrow’s Jewish leaders will also come out of the movement. Before he left, Glick said he hoped to soon “activate in a more formal way,” with official leadership positions, chapters and campus clubs.

“I’d be very concerned by what Betar US has planned,” Myers said, calling the group’s beeper drops “very scary.” Recently Netanyahu offered his own version of a beeper joke, giving Trump a “golden pager” during his recent state visit.

“It seems we’re half a step away from physical violence,” Myers said. “And I would say, if there are respectable parties left in the Jewish community, this is a moment of reckoning, to say, ‘Wait a minute, this is going way too far.’”

Glick said he knew that Betar is not where the Jewish mainstream is. But like the Betaris of old, he sees them as doing the dirty work the rest of the Jewish people is too scared to do.

“When I go to synagogue, I can’t tell you how many Jews give me a hug, give me a handshake, give me a pat on the back,” Glick said. “Out of one side of their mouth, they’re like, ‘Oh my God, you’re meshugenah. This is too aggressive. It makes us look bad.’

“And on the other side of their mouth, they’re like” — and here his voice dropped to a whisper as he imitated his scared fellow congregants — “‘Thank you very much. We need you.’”