During his presidential campaign, Donald Trump proclaimed at a rally that Hillary Clinton “got schlonged” in the 2008 primaries. Schlong, when used as a noun, is a Yiddish word for penis—and a pretty vulgar one at that. But when used as a verb, is it even a word? Should it be considered a misogynistic insult? A malapropism? Turns out, it’s all of the above. While Trump defended his choice of words on Twitter, commentators like Frank Rich argued that “get schlonged” is used as a regional equivalent of “screwed” in New York (particularly in Long Island and Queens). But it’s also possible Trump simply made a mistake. As language expert Steven Pinker told The Washington Post, many non-Jews “are confused by the large number of Yiddish terms beginning with schl or schm.”

Probably the most common schm- Yiddishism is schmuck. Another word for male genitals, schmuck is used all the time in English to describe someone who is foolish, obnoxious or detestable. Actor Harrison Ford made headlines last spring when, while landing his small plane at a California airport, he unwittingly touched down on the taxiway instead of the runway. Immediately realizing his mistake, he told air traffic control: “I’m the schmuck that landed on the taxiway.”

While pretty much everyone—even non-Jews—knows that schmuck is Yiddish, few know much about its etymology. The word derives from shtekele (Yiddish for little stick), which turned into shmekle (a baby-talk equivalent of pee-wee or weenie), according to Michael Wex, author of the popular Yiddish primer Born to Kvetch. Just as shtekele became shmekle, shtok—a word for stick or club—became schmuck. But while “the shm– prefix makes diminutives like shmekl and shmekele cute and harmless,” schmuck is considered obscene.

English speakers like Ford, who treat the word as a benign throwaway, have no idea how vulgar the word is considered among Yiddish speakers. As linguist Paul Glasser says: “You can say schmuck in relatively polite company in English—you can’t do that in Yiddish.” Because schmuck is so vulgar, Yiddish speakers have traditionally invented workarounds so they don’t have to say it outright. Some say shin mem kuf (which is how the word is spelled in Hebrew), while others use a tongue-in-cheek phrase like Shmuel Mikhl Kalmen (the first letters of each of these men’s names spell schmuck). Another acronym is Shabbes Mikro Koydesh (Shabbat, Bible and holy). “Somebody must have thought that was really clever, to take these very sacred words and turn them into a vulgar insult,” says Glasser, who co-edited last year’s Comprehensive English-Yiddish Dictionary. Sometimes, the workarounds can be equally—though differently—offensive. Glasser compares them to leaving a tip at a restaurant: If you don’t tip, that’s insulting. But if you leave only a penny? That’s even worse.

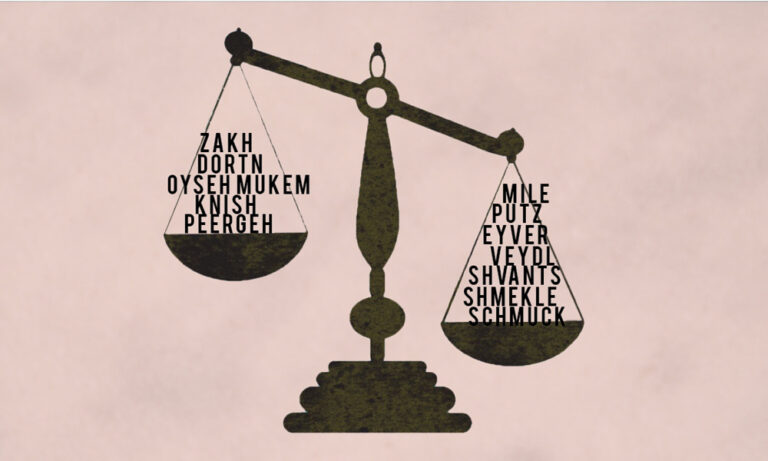

The many Yiddish words for male genitalia can be confusing to English speakers. Like schmuck, putz is also more offensive in Yiddish. The two words are similar, but not identical. “You can call someone a ‘poor schmuck,’ even feel like a schmuck yourself; a putz is vicious and always someone else,” Wex writes. But while some of these words are vulgar, others are clinical, humorous, conversational, euphemistic. There is a word to fit seemingly every context: In polite conversation, the term of choice is eyver. Because eyver can also be used to describe an arm or a leg—similar to “member” in English—its exact meaning depends on context clues. Mile, which means circumcision, is another inoffensive option, and “a fine example of using a part of something to represent the whole,” Wex writes. “It tends to be the preferred term among religious people who need to mention such things.” Looking for a Yiddish equivalent of “dick” or “jerk”? Try shvants or veydl, which are both Germanic words meaning “tail.” One might use these words in a fit of road rage, according to Wex. “The guy who cuts you off because he doesn’t notice that you’re there is a veydl, the one who does it to spite you is a shvants.”

All of this begs the question: Why does Yiddish have so many words for penis? According to Sarah Bunin Benor, professor of contemporary Jewish studies at Hebrew Union College’s Jewish Institute of Religion, “it is common to have many words for genitalia in any language because it’s a taboo subject, and there are often euphemisms.” This is also true in Hebrew, which has an equal abundance of words for penis. These words develop cyclically: Once a particular euphemism catches on, it eventually becomes taboo or improper itself, and a new euphemism develops in its place. Haaretz’s Elon Gilad calls this phenomenon “euphemism creep,” noting that even the Bible is full of euphemisms for penis, like erva (nakedness) and yad (hand).

But even though Yiddish has a lot of words for genitalia, it doesn’t have more words than other languages, says Yiddish language specialist Noyekh Barrera. To find the multitude of English equivalents, Barrera says, “one need only look in the Urban Dictionary.” Nor is Yiddish bereft of words for female genitalia, although they are markedly less flashy. Some fall into a category Glasser calls “learned words,” like oyseh mukem (that place) or mokem haturpe (place of weakness). These are words that come from Hebrew, “which means that, unless you’re really scholarly, you might not even understand them,” says Glasser. There are also food words, such as peergeh (pierogi) and knish (literally just knish), both similar to “pussy” in English, according to Wex. Some of the most interesting euphemisms don’t mean much of anything: Choice examples include zakh (thing) and even the simple dortn (there).

Yiddish words for female genitalia are far less likely to end up in a joke, and they are rarely traded as insults. Why the discrepancy? For most of its history, says Glasser, Yiddish was spoken among communities that adhered to traditional gender roles. In the Yiddish world—and in Yiddish—women are treated with a “mixture of respect and condescension,” he says. It’s as if women “have to be protected,” but for men, “pretty much anything goes.”—Ellen Wexler