Coining the Canon

by Marilyn Cooper

When biblical scholar Elsie Stern lectures about the ancient world at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, the first thing she does is hold up a Bible and tell her students, “For most of the first 3,000 years that these words were around, if you said ‘Bible,’ no one would have any idea what you were talking about.”

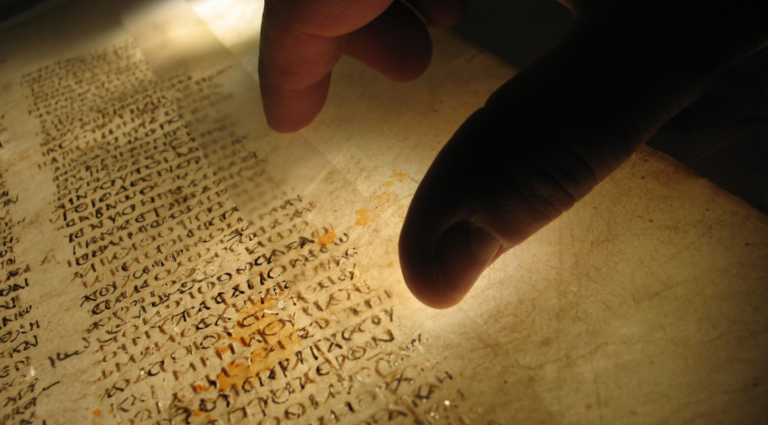

What most of us know as the Bible began as a collection of ancient teachings and manuscripts that, starting roughly between the 15th and 14th centuries BCE, were gradually codified by a series of unknown authors working in different locations over the course of 16 centuries. Like most other ancient works, it did not have a name. In short, the best seller of all time is also the greatest untitled work in history, which gives rise to a modern conundrum: What should we call it?

The earliest known name for the ancient Hebrew writings that comprise the Jewish canon is Torah. Stemming from the Hebrew root y-r-h—literally meaning “to shoot,” or “to hit a mark”—Torah is understood to mean “teachings” or “instruction.” In the most limited sense, Torah refers to physical scrolls or to the Five Books of Moses: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. But the word “Torah” can also indicate the complete canon of Jewish texts, also called the Tanakh, which is an acronym of the first Hebrew letter of each of the groupings of texts: Torah (the Five Books of Moses), Nevi’im (Prophets) and Ketuvim (Writings). Most broadly, it can refer to the entire Jewish worldview and lifestyle. “Torah doesn’t just mean the Five Books of Moses, but an embrace of the whole Jewish tradition,” says Modern Orthodox Rabbi Irving (Yitz) Greenberg.

The names we use for these writings sometimes reflect the convoluted process of their canonization, says Robert Alter, professor of Hebrew and comparative literature at the University of California, Berkeley. Among the inhabitants of the Kingdom of Judah exiled to Babylonia in 586 BCE were scribes and scholars who edited and collated both the Five Books of Moses and a large number of other Hebrew and Aramaic texts to ensure survival of their national identity. When they returned to Zion in the 5th century BCE, they brought these texts with them, and Ezra the Scribe instituted the practice of public readings of the Torah. These texts began to be called the Mikra, meaning “that which is read”—a term still used in modern spoken Hebrew.

Beginning in 3rd-century Alexandria, Hellenistic Jews translated the Tanakh into Greek to create the Septuagint, which included books that did not become part of the Jewish canon, such as Maccabees and Judith. This became the basis for the Christian version of these texts. In the Septuagint, Jews translated the Hebrew word b’rit as the Greek distheke, which can mean either “covenant” or “last will and testament.” In the earliest Christian version of these texts, the Vetus Latina (350 CE), the word was translated as the Latin testamentum, meaning “testimony.”

The idea of an “old” testament comes from the 31st chapter of Jeremiah, which reads, “Says the Lord, the day will come when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and the house of Judah, not according to the covenant that I made with their fathers in the day that I took them by the hand to bring them out of the land of Egypt, for that covenant they have broken.” While Jews understand this to mean the covenant at Sinai, Christians interpret the new covenant to foretell the coming of Jesus and a time when the laws given at Sinai will be replaced by new ones. By the end of the 14th century, the term “Old Testament” was widely used by Christians.

The term “Bible” also first came into usage during this period. Deriving from the Konic Greek word biblion, meaning “paper” or “scroll,” Bible entered the English language by way of the Latin word for book, biblia. Originally, in the Middle Ages, “bible” referred to any physically large book, not just the sacred texts.

Today, there is a debate over whether the name “Old Testament” is appropriate or derogatory. Within many Christian communities, particularly Evangelical ones, “Old Testament” remains the unquestioned term of choice. Christian author Chuck Northrop says that this is because the Old Testament or old covenant was “written as a shadow of a new and better one, the New Testament.”

Many Jews, however, strongly object to the term. Rabbi Michael Berenbaum, professor of Jewish studies at the American Jewish University, says Old Testament is offensive because it “reflects a solely Christian viewpoint in which the New Testament supplants and adds to an older one.” Rabbi James Rudin, who is noted for his work on interfaith relations, agrees: “I abhor the term ‘Old Testament’; [it suggests] that Judaism has been replaced.”

To some, what’s actually at stake is the larger issue of who owns the texts. “Those who support calling them ‘Old Testament’ basically believe that practicing Jews of today do not understand the full thrust of their own scriptures,” says Alter. “In using ‘Old Testament,’ they are saying, ‘We have taken over ownership of the Hebrew scriptures because we are the only ones who fully comprehend what they really are.’”

Most scholars today support calling these texts the Hebrew Bible, a name favored for its neutrality: It simply describes the language in which the majority of the texts were written. Other suggestions include “First Testament” or “Early Scriptures.” Stern says that her preference would be to call them “the remaining Israelite library” but adds that, much as Winston Churchill called democracy the worst form of government except for all the others, “‘Hebrew Bible’ is the best choice out of a range of highly imperfect options.”—Marilyn Cooper

Please rewrite the following sentence:

Original: “The cat jumped onto the table and knocked over a vase.”

Rewritten: “The cat leaped onto the table and toppled a vase.”

Source link