Who’s Afraid of the Evil Eye?

by George E. Johnson

In 2004, the stoic, cowboy-esque Clint Eastwood unexpectedly proved himself more Tevye the Dairyman than Dirty Harry. In response to a reporter’s question about the chances of his movie, Mystic River, winning the Best Picture Oscar, Eastwood cried, “Kinehora!” He explained that it was a Jewish expression used to ward off a jinx, one of countless protective folk actions intended to avoid, fool or attack evil spirits.

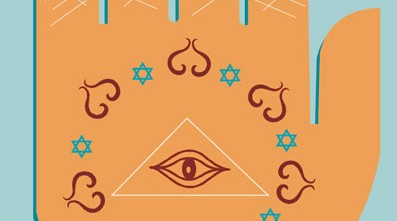

Kinehora is a contraction of three Yiddish words: kayn ayin hara, literally “not (kayn) the evil (hara) eye (ayin).” The kayn comes from the German for “no” and the ayin hara from Hebrew. The evil eye is one of the world’s oldest and most widely held superstitions. Its place in Jewish lore is rooted in classical Judaism and Jewish folk religion dating to the Bible, the Talmud and rabbinic Midrash. There’s a rich history, particularly from the Middle Ages onward, of often bizarre and elaborate folk practices—invocations such as kinehora being a rather tame example—aimed at thwarting the malicious intent or effect of the evil eye.

The evil eye stems from the Greek theory that the eye can shoot rays that strike with harmful or deadly force. In Greek legend, for example, the monster Medusa can turn a man into stone with a single glance, says Richard G. Coss, author of Reflections on the Evil Eye. This capability is known as jettatura, a Latin term for a malevolent gaze with the power to harm, according to Alan Dundes, the late folklorist from the University of California, Berkeley, in an essay, “Wet and Dry: The Evil Eye.”

The evil eye may have been introduced into Jewish thought by Talmudic authorities exposed to Babylonian culture, according to Joshua Trachtenberg, the late author of Jewish Magic and Superstition: A Study in Folk Religion. The Babylonian Talmud claimed that there were rabbis who had the power to turn a person into a “heap of stones” with just a glance. Sefer Hasidim (The Book of the Pious), a 12th-13th century guide to Germanic Jewish religious practice, similarly warns, “angry glances of man’s eye call into being an evil angel who speedily takes vengeance on the cause of his wrath.” Dundes also links jettatura to liquids, including water, wine, saliva and even semen, which were thought to protect (either as a weapon or a shield) against the evil eye. (This may be an origin for the practice of spitting three times—or saying “ptoo, ptoo, ptoo”—in response to expressions such as kinehora.)

The power of liquids is reflected in the Talmudic interpretation of Jacob’s biblical blessing of Joseph: “Just as the fishes in the sea are covered by water and the evil eye has no power over them, so the evil eye has no power over the seed of Joseph.” The pervasive use of fish imagery and amulets in the Middle East and North Africa can be linked to this and similar sources.

The fear of being the object of other people’s envy is “the common societal root of fear of the evil eye” across diverse cultures, says Boris Gershman, professor of economics at American University. This concern, which Trachtenberg calls the “moral” version of the evil eye, “can be traced to the pagan conviction that the gods are essentially man’s adversaries, that they envy him his joys and his triumphs, and spitefully harry him for the felicities they do not share.”

This idea is also common in Jewish texts. It’s found in Midrashic tales such as Sarah casting the evil eye on Hagar, and Jacob hiding Dinah in a box to protect her from Esau’s evil eye. It’s also in rabbinic literature: Johanan ben Zakkai, in the Ethics of the Fathers, asks his disciples which character trait a person should most shun. Rabbi Eliezer responds that an evil, or jealous, eye is the worst quality; Rabbi Joshua says that the evil eye will cause a person’s early death. The Babylonian Talmud warns the owner of a beautiful coat to keep it hidden from the potentially envious eyes of a visitor, and cautions against overly admiring another’s crops lest the evil eye damage them. In these cases, behaviors and traits—not sayings or talismans—are seen as the best protection from the evil eye.

While the idea of the evil eye is ancient, the term kinehora came later. It was likely first used in medieval Germany, as a translation from the Hebrew b’li ayin hara, according to Rivka Ulmer, professor of Jewish studies at Bucknell University and author of The Evil Eye in the Bible and Rabbinic Literature. German Jews encountered it in the numerous religious pamphlets of Psalms and other prayer books produced for women in Yiddish. Its use was so widespread that German neighbors started using equivalents of kinehora, like unbeschrieen (“this is not to be mentioned”), and unberufen (“we don’t call up the evil eye”), which are still used today. From the 17th century onward, according to Trachtenberg, “no evil eye” expressions had “become automatic accompaniments on Jewish lips of the slightest compliment.”

This lasted, however, only as long as the Yiddish language flourished. “Compared to contemporary English,” writes Michael Wex in Born to Kvetch, “Yiddish is a regular haunted house where demons frolic and sinister forces rage nearly unchecked.” In modern times, says Sarah Bunin Benor, professor of Jewish studies at the Hebrew Union College and author of the Jewish English Lexicon, kinehora and b’li ayin hara are used mainly by Orthodox Jews in the United States and Israel.

Today, belief in the evil eye is very low—according to the Pew Research Center, only about 16 percent of Americans take the idea to heart. Still, the use of protective amulets and talismans, protective expressions such as “knock on wood,” sales of hamsas (perhaps accompanied by a complementary red “kabbalah” string) and eye jewelry do not seem to be decreasing. As the Sefer Hasidim would say: “One should not believe in superstitions, but it is best to be heedful of them.”