For the past six weeks, members of Beth Sholom Congregation & Talmud Torah in Potomac, Maryland, have attended services in the parking lot. Sitting eight feet apart with masks donned, or in a designated car area with their windows slightly cracked, they listen and sing along to Rabbi Nissan Antine’s prayers. Even through extreme heat or rain, they do what they can to be together safely.

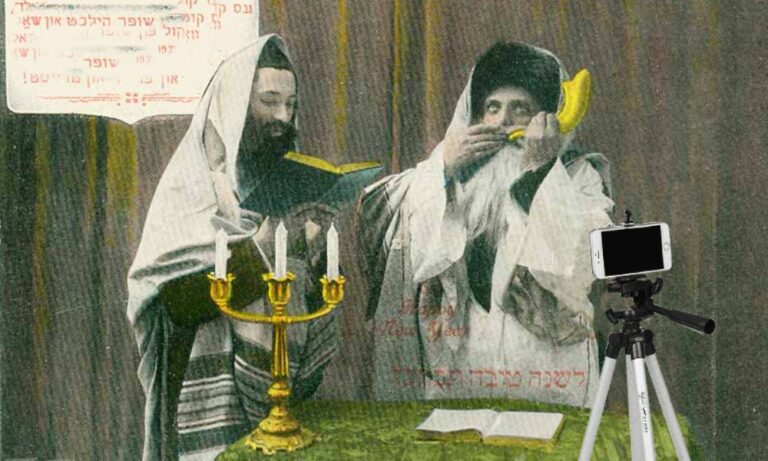

From Zoom services to occupying alternative outdoor spaces, congregations across the country have come up with ways to adapt to the challenges of COVID-19. And with the High Holidays, a pivotal time in the Jewish calendar, quickly approaching, synagogues are grappling with both Jewish law and congregants’ needs.

Individual synagogues have looked to denominational organizations or governing bodies for guidance. But those guidelines leave grey areas: On shortening services, for example, the Rabbinical Assembly of the Conservative movement wrote in an unofficial statement that “making decisions about liturgical abbreviation is challenging in part because so many of the beloved parts of our liturgy, and the liturgy for the High Holy Days, do not have the status of halakhic requirements.”

A central issue for more observant denominations has been the use of technology. Zoom services entered the Jewish world in full force on Passover. While many Conservative and Reform rabbis embraced the video-calling services, some Orthodox rabbis have clashed over whether one can use Zoom on the holiday, Throughout the Orthodox and Modern Orthodox community, using any form of technology on Shabbat and certain holidays is prohibited, unless a life is at risk.

“Any services that we want to offer on the [High Holidays] will have to be in person, and there’s a strong demand for services,” says Rabbi Shaul Robinson of Lincoln Square Synagogue, a Modern Orthodox congregation in New York City. “They’re going to have to be shorter and all the spaces we’re using in the buildings and outdoors will be socially distant, but we are going to be providing services for everyone in the community who wants in-person services.”

In statements and guidelines regarding COVID-19, organizations representing the three major American Jewish denominations have all referenced the concept of pikuach nefesh, “safeguarding life,” which is considered to supersede almost all other Jewish laws.

To Rabbi Justin David of Congregation B’nai Israel, a Conservative synagogue in Northampton, Massachusetts, pikuach nefesh means that in-person services are impossible during this time. B’nai Israel has converted to entirely Zoom and Facebook live-streamed services and will do the same for the High Holy Days.

“This has given us as a community an opportunity to see ourselves not just as ourselves, but really to see our lives as intertwined with other people’s lives, because our health is not only for us, but it’s for a community. And the risks we take are not only our personal risks but risks for the community,” David says.

As early as May, Conservative Rabbi Mario Rojzman announced to his congregation at Beth Torah Benny Rok Campus (BTBRC) in North Miami Beach, Florida that High Holiday services would be held virtually, with some parts pre-recorded. Rojzman said BTBRC is among the most traditional of the Conservative movement; the synagogue still doesn’t play music on Shabbat. But he cited the Jewish principle of hora’at sha’ah (“the ruling of the hour”) to bend Jewish law during times of extreme circumstance.

“Halacha was always a working process …We [Conservative Jews] are the ones that always are trying to be modern sometimes and traditional sometimes. And this is the time to apply the maximum towards modernity to give a traditional message,” Rojzman says.

That distinction of hora’at sha’ah also prevents sending a message of permanent change in Jewish customs. For Modern Orthodox communities such as Antine’s, a shifting paradigm would weaken these traditions’ underlying values.

“What I was very concerned about was not creating a new way and for it to be like that forever, because I think it’s very powerful when someone has a Yahrzeit or has to come to the synagogue and pray together and afterward someone comes up to them. That’s how you create community around hard things, around happy things,” Antine says. “You want to use Zoom to provide people with what they need, but on the other hand, you don’t want to lose a sense of community.”

For Rabbi Shoshanah Conover of Temple Sholom, a Reform congregation in Chicago, challenges arose in emulating the High Holidays’ innate significance to the community, rather than its halachic requirements. Temple Sholom is avoiding pre-recorded services to ensure congregants maintain an authentic connection with the holidays.

“Having that touchpoint of community, of the music and the elevation that provides, and also having a sense of that wisdom—that while some of these prayers were written hundreds, or even more years ago, they have this wisdom that feels relevant for right now—I think that people need all of that at once,” Conover says.

So, while Temple Sholom’s services will largely be over Zoom, Conover is seeking to create a sense of togetherness through High Holy Day bags, complete with the physical machzor (holiday prayer book), yizkor and havdalah candles and toys for families with small children.

Congregants will be able to pick up the bags before Rosh Hashanah and interact with clergy in a drive-through celebration.

Outside of traditional ritual practices, synagogues are exerting even more effort to capture the needs and desires of their unique congregations. Since about one-third of BTBRC’s congregation speaks Spanish, Rozjman plans to pre-record Spanish-language services alongside their main service. Congregation Ahava Achim, a Sephardi Modern Orthodox synagogue in Portland, Oregon, typically reads segments of the services in Ladino. But due to a truncated service, President Renee Ferrera says they won’t be able to do so this year.

As Temple Beth Shalom in Potomac, Maryland gears up to offer 12 shifts of services (with a combination of venues and Sephardi and Ashkenazi stylings), Antine said he’s been searching for a silver lining amid this year’s multitude of changes.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about the idea of how people are saying it won’t be perfect this year. But I’ve been thinking, ‘No, it’s going to be perfect for this year.’ This is how things are,” Antine says. “I’m very sad for people who are elderly or can’t come…But for the people who can do it, I’m not sad that it might be a little too hot or a little too cold. It shakes things up in terms of our religious experience. And I know for me, personally, some of my most meaningful davening and praying have been over the past few months, outside in the pouring rain in a thunderstorm.”

Moment brings you essential independent reporting from the Jewish community and beyond. But we need your help. Your support is critical to the work we do; every tax-deductible gift, of any amount, keeps us going. Thank you for reading and thank you for your help. Donate here.