The page of the daf yomi that was read around the world on the first Shabbat after the first yahrtzeit of the people who died in the Simchat Torah tragedy (Bava Batra 123) triggers some thoughts that are of particular relevance as the Israelis decide on the next steps to take in the ongoing response to the tragic events of Simchat Torah 2023.

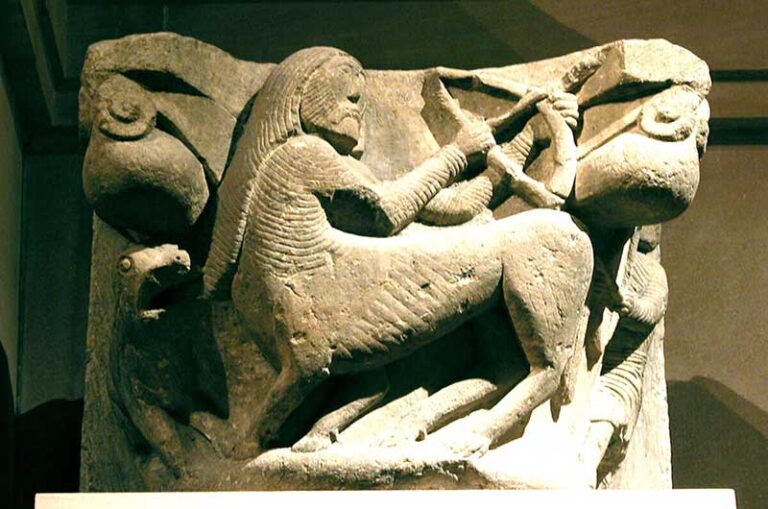

Jacob is cited in the Torah in reference to Shechem, a city in Israel once occupied by people that might be compared to Hamas of today â or hopefully only of yesterday â which Jacob said he took out of the hands of the Amorite âwith my sword and with my bow [as in bow and arrow]â (Genesis 48:22). We are talking, of course, about the man described as Ish tam, yoshev ohaleem (a simple person, or a straightforward person, or a complete person, who dwelt in tents).

Predictably, the Talmud continues, âBut is it so that Jacob took the portion (of land) with his sword and with his bow? Isnât it already stated, âThrough You do we push down our adversaries; through Your name do we trample those that rise against us. For I trust not in my bow, neither can my sword save meââ (Psalms 44: 6-7).

The Talmud goes on to explain that âswordâ refers to prayer, and âbowâ refers to petition (prayer being further described as public prayer formulated for the congregation to say in unison, and petition described as private prayers added on an individual basis). It has been observed that had the sword been meant literally, the enemyâs allies would have joined. Sound familiar? This introduces us to the classic balance in Jewish life between bitachon (faith) and hishtadlut (making an effort as long as it is realistic), which complement each other.

As an aside, the official exposition of the pshat (âplainâ meaning) in the Torah known as the Targum Onkeles (35-120 C.E.) cited by the Meshech Chachma (1843-1926) (as I heard it from Rabbi Sholom Rosner, seven and a half years or so ago) on the sword and the bow discussed above refers to them as bitslussi uâvâussi, prayers and supplications, which corresponds to the language in the Kaddish prayer recited by the chazzanim and the mourners in shuls throughout the world a few times a day every day, where we ask for our prayers and supplications to be accepted. With this in mind, now many of us may know for the first time in our lives what we mean in the Kaddish when we pray for tzlosâhon (fixed prayers) and baâusâhon (personal supplications) to be accepted!

As a further related aside but with practical applications, the Meshech Chachma notes that prayers formulated by our rabbis generations ago may be accepted even if recited by rote without appropriate kavanah or intent (although of course proper intent is preferable), as opposed to personal requests which require â and are more likely anyway to have â specific adequate intent. The prayers generated by our rabbis are compared to swords that are inherently sharp and effective as is, while the supplications added in an improv manner by individual worshippers seeking divine providence are compared to bows which are inherently harmless â and useless â unless extended and used with arrows with human initiative. The harder the archer pulls back on the bow, the further the arrows go to their targets. The stronger and more heartfelt the personal supplications, the more likely they are to make their mark and reach G-dâs âheartâ (so to speak) in Heaven.

Extending the contrast further, since a sword can be deadly to the touch (if touched at the ârightâ place on the body and on the sword) it can be compared to a conservative or defensive stance, where offense is not as crucial, while the harmless bow and its modern successors (until activated) can only be effective with a pre-emptive launch, which the Israelis were famous for in the Six-Day War, and again more recently with the pagers and assassinations, let alone what they are yet to do versus Iran and/or Lebanon in the future.

Now, back to the sword and the bow as they relate to prayers and supplications. It seems that there is a vital place for everyone, the soldiers on the battlefield, and the worshippers in our shuls. If we take the reference to the sword and the bow literally, we need to adapt the imagery to todayâs times anyway. The Israelis are confronted with the decision as to whether to fight with the modern counterparts of the sword or with the modern counterparts of the bow and arrow. The sword is a direct approach, fast and to the point, but limited in scope. The bow and arrow are more nuanced â how far to pull back in order to generate the pressure to strike back in a shorter distance, for example, in Lebanon, or a longer distance, for example, with Iran.

In discussing the swords, the bows, and the arrows, we may also note that the only time we read of Jacob actually fighting in the Torah, in any depth or detail, he was fighting an angel, and with no weapon at all.

Chalk one up for a hybrid approach with features of reliance on prayer and on physical strength, or, once again, bitachon (faith) and hishtadlut (making an effort).

We may also note that when Jacob and his family were leaving Lavan and preparing to meet Jacob’s brother, Esau, Jacob strategically organized his family so that the stronger members of his family would be exposed first to protect the weaker members of his family, the exact opposite of the approach of Hamas in using human shields.

An actual battle with Jacob’s brother was seen as a last resort, after prayer and gifts. Note the juxtaposition but in a different relationship between prayer and physical fights, this time with gifts thrown into the mix. It is interesting to note that right after Sinwar was cut down as the head of Hamas, the Israelis officially offered Gazans the gift of free passage out of Gaza to freedom and safety in exchange for the release of hostages, and a rich American offered cold hard cash. But if the hostages will not be released one way or another, the last resort will be to continue – the war to rid Israel of existential threats and to liberate the hostages.

We pray that our continued prayers together with deterrent-intended military initiatives will contribute toward peace in the Middle East, so that new generations of weapons will not be needed to protect new generations of Jews and Arabs.