It was a saying among the people of Old Jerusalem: the character and fear of heaven of the bookseller was sometimes no less important than the books he had on offer. So felt many of those who came to buy from the book-and-Judaica stall in the Machane Yehuda market, which was operated for most of the British Mandatory period by two partners who were also talmidei chachamim: Rabbi Yosef Yitzhak Shloush and Rabbi Amram Aburbeh.

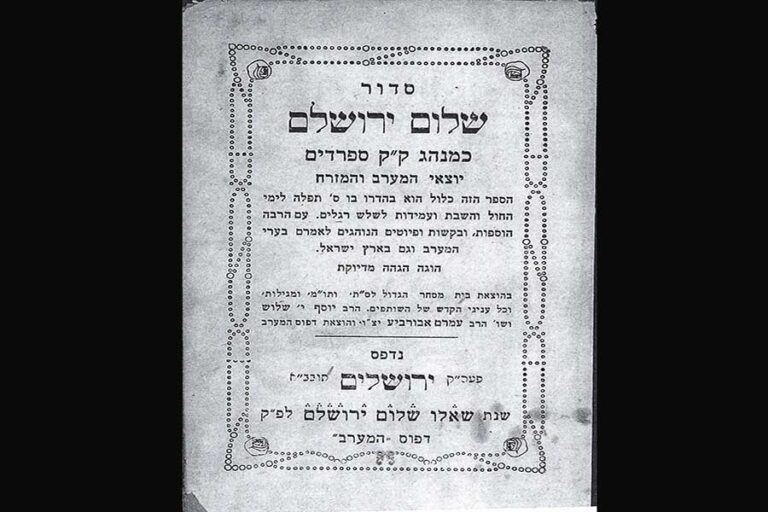

A look at the catalogue released by the two around 1930 shows that the small store â which the two had acquired from sofer Rafael Ben Naâim â included âsifrei Torah, tefillin and mezuzahs, megillahs and tzitziyos and shofaros, and shechting knives and sharpening stones, and siddurei tefillah and other sifrei kodeshâ for purchase. One of the siddurim they sold was the one the two they themselves had produced in 1933 â the Shalom Yerushalayim siddur.

The decision of the two Torah scholars to work together was natural, in retrospect: they both had a fairly similar life path, and both made a principled decision not to make a living from their learning, and instead provide for themselves with trade and extensive public activity. Both Rabbi Aburbeh (1892-1966) and Rabbi Shloush (1891-1960) were born in Morocco to families of Torah scholars, and both made aliyah to Jerusalem with their families when they were young.

The two later learned and then taught at some of the most prominent yeshivos in town, including the Sephardi yeshiva Porath Yosef and the Maâaravi (i.e., North African) Tuvi Yisbaâu, while also becoming part of the local public and rabbinic activity at the Vaâad Edat Hamaâaraviyim (Committee of the Community of Westerners) and in leading the local community. The two later also served as sheluchim or shadarim of their community to the communities throughout North Africa, and in the latter part of their lives they also served as local Rabbis: Rabbi Aburbeh as the Sephardic rabbi of Petah Tikvah and Rabbi Shloush as the rabbi of the Maâaravi community in Jerusalem.

The Shalom Yeushalyim siddur the two produced â like most of the Sephardi siddurim of the time â was relatively small and included two main parts: 155 pages which included all prayers for weekdays, Shabbat, and holidays, and 24 additional pages entitled âSefer Tehillot LaâE-lâ or Book of Praise for G-d. The latter included piyyutim or religious poems and requests for the holidays â some in Hebrew and some in Judeo-Arabic.

The siddur itself was Sephardi for all intents and purposes, but its subheading â âaccording to the minhag of the holy community of Sefardim of the Maâarav and the Mizrachâ â hinted at Rabbi Aburbehâs principled and consistent ideological line, which strove already at this early date to fuse all existing Sephardi and Mizrahi prayer nusachim into a single, unified prayer formula. His approach was to subordinate all non-Ashkenazi prayer formulas to the local Sephardi custom of the Land of Israel, which heâd become acquainted with while growing up in Jerusalem.

Thus he tended to stress that the siddur included âmany additions, requests and piyyutim which are customarily said in the cities of the Maâarav, and also in Eretz Yisrael.â Rabbi Aburbehâs approach, it should be noted, was close to that of Rabbi Ben Tziyon Meir Chai Uziel, with whom he was in contact, and he published a book called Nesivei Am towards the end of his life, where he further developed his approach to spiritual and religious mattes. Itâs interesting to note that his public influence did not die with him: in 1976, the Mizrahi version of the Rinat Yisrael siddur was published. Its editor, Shlomo Tal, relied greatly on Rabbi Aburbehâs comments on the nusach and customs mentioned for this siddur.

The siddurâs graphic design was quite aesthetically appealing: the letters were largely clear and sharp, the fonts were fairly advanced, and the vowelization and brief prayer instructions were also well done. Despite all this, it was not a hit: although copies were sent abroad and were sold in the bookstore of Hacham Maimon Ovadyah in Sefrou, which is close to the city of Fez, the siddur only had a single edition, and can only be found in a few libraries today.

Still, the two continued their work in the world of shuls over the years. Of Rabbi Shloush, who lived in the neighborhood of Machane Yehuda, it was said that he would divide his Shabbat prayers among all the Maâaravi shuls in Jerusalem so he could meet with all members of his community, while Rabbi Aburbeh would become of the founders of the Great Synagogue of Petah Tikvah.

Even before this, he printed a number of additional siddurim in Jerusalem. One of these was a local version of the popular âTefillas Benei Tziyonâ and another siddur he printed in 1942 â apparently a complete version of the original siddur he created with his partner. Thus, even if Shalom Yerushalayim did not succeed as much as it might have, the work of its two authors in the field of the prayer nusach of Eretz Yisrael is very much worth learning about.

This article was originally published on JFeed.com.