Last week we saw how Rav Kook views teshuva as an inexorable process of redeeming the world, and how the penitent one becomes a participant in this process. We will turn now to see some of the mechanisms by which this comes about, both those that are at work in the world and those emerging from the souls of the righteous.

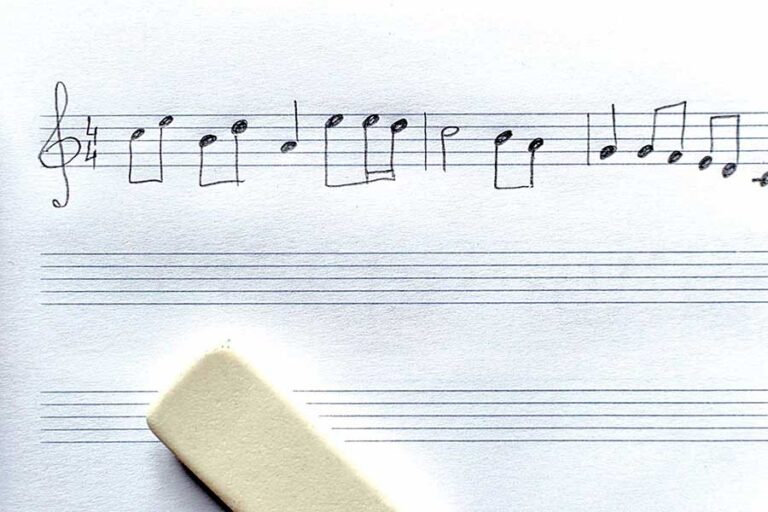

Rav Kook speaks evocatively of a world full of harmony. Everything has been created with a purpose and situated in such a way that it stands in perfect balance with everything else. The many âvoicesâ of creation are carefully brought together and blended such that the emerging âmelodyâ of human experience is made greater by the diversity of voices comprising the chorus.

But the Divine Wisdom maintains this balance, this harmony, even when one of the voices sings out of tune. When an individual deviates from the Divine plan that has been set out for its own benefit, that individual feels the distress that comes with sensing distance between oneself and oneâs Creator. For the righteous this sensation is acute and agonizing, but even those who have become inured to the spiritual numbness of a life spent without holiness or purity still feel on a deep level the presence of an unmet need. When we transgress, we humans suffer as a result of our transgression. We introduce misery and distress into the world when we fail to adhere to the path of light and growth that has been prepared for us by our Creator.

But the wise also see that the suffering serves a purpose beyond merely reminding us to do good and avoid evil: The suffering itself offsets the deviation of the evil we perpetrate, and through the blending of error and consequence, a new harmony is achieved. Thus, the balance always remains.

For the one who understands how such deviation creates barriers between the soul and the source of all life, the separation is experienced as greater suffering, causing more profound distress than anything in the material world. For such an individual, the process of return and the erasure of this barrier is the greatest joy, and it leads to a state of transcendence where the one who does teshuva is more radiant, more resonant, than one who never erred at all.

This requires true regret and personal transformation, such that the one who did the wicked acts would not ever act in that way again. The mind and the heart have to truly feel the remorse, and the intellect has to understand why and how such conduct must always be avoided in the future. But this is because of the disruption of the Divine order, the dissonance in the symphony of being that has been caused by our transgression. When a person truly understands the harm they have caused and regrets it and returns to consonance with the Divine Will, then they remain a more willing and more effective instrument for the transmission of the light of Hashem that brings revelation and ultimately redemption of the individual as well as the collective.